Artworks

Erich Ohser, called E.O. Plauen (1903 – 1944)

Portrait of Erich O’Krent

Pencil, wash and collage on paper

23.5 x 32 cm. (9 ¼ x 12 ¼ in.)

Provenance:

Francis Barillet, Paris.

Portrait of Erich O’Krent

Pencil, wash and collage on paper

23.5 x 32 cm. (9 ¼ x 12 ¼ in.)

Provenance:

Francis Barillet, Paris.

Who is Erich O’Krent? With his gaunt features, elongated pipe and tilted homburg, he has the look of an overworked but astute detective from the closing years of the Weimar Republic, of a type made famous by Volker Kutscher’s recent Babylon Berlin series. In fact, Erich O’Krent is almost certainly the alter-ego of the similarly overworked but astute journalist, poet, satirist and six times Nobel Prize nominee Erich Kästner (fig. 1). O’Krent and Kästner share not only the same Christian name but also close initials, as well as their very similar and distinctive features, even if these have been exaggerated by Erich Ohser in this satirical depiction (fig. 2). Furthermore, Kästner and Ohser visited Paris together in May of 1929: not only does the present work come from a Parisian collection but it was also acquired alongside a sketch by Ohser from 31st May 1929, which depicts a flower-seller in Gare du Nord and has ‘Okrent’ inscribed on the backing paper. Perhaps the guise of Erich O’Krent was humorously created by the two friends on this very trip.

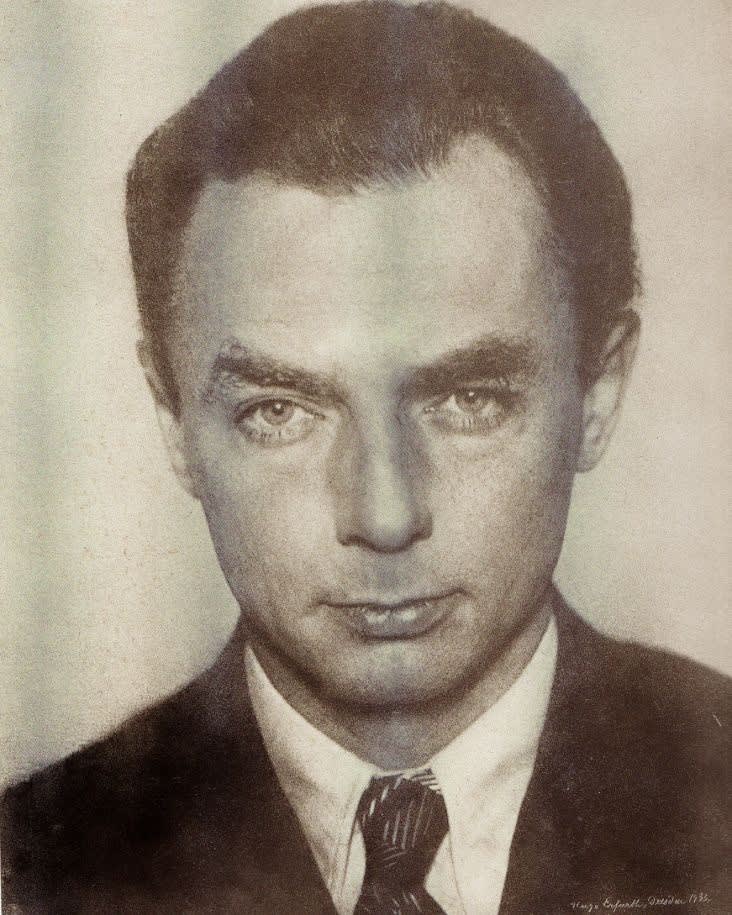

Fig. 1, Photograph of Erich Kästner, 1933

Fig. 2, Photograph of Erich Ohser, 1943

Kästner and Ohser had met in Leipzig in the early 1920s whilst working on the local newspaper together, the Neue Leipziger Zeitung. Alongside their editor, Erich Knauf, they were known as the ‘three Erichs’, sharing a biting wit, modern sense of aesthetics and like-minded political ideologies. The publication of an erotic poem by Kästner, with illustrations by Ohser, led to the journalist’s dismissal from the newspaper in 1927 and subsequent departure to Berlin, where he would be joined a year later by his two friends. These Berlin years, until the demise of the Weimar Republic in 1933, were extremely productive for Kästner, who published his best-known work in 1928, the massively popular children’s book Emil and the Detectives, and wrote hundreds of poems and articles, often under pseudonyms.

As outspoken opponents of Nazism, the coming to power of Hitler in 1933 would make life extremely difficult for the ‘three Erichs’, and would eventually prove fatal for two of them. Knauf was arrested in 1934 after a negative review of Carmen at the German state opera angered Göring. Expelled from all professional associations, Knauf was interned for three months at Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Kästner, interrogated by the Gestapo several times, was expelled from the national writers’ guild and his books, deemed contrary to the German spirit, were destroyed during the Nazi book burnings.

Ohser earned a particular enmity from the Nazis for his satirical depictions of Goebbels and Hitler, exposing their megalomania through effective caricature. Like his two friends, he was also banned from his profession and had to operate under the pseudonym E.O. Plauen (his initials and the town of his childhood). Between 1934 and 1937 Ohser created his beloved and internationally famous cartoon series Father and Son (fig. 3), a wordless and carefree narrative of a father and son grappling with everyday situations. Plauen was eventually arrested with Knauf in 1944 for expressing anti-Nazi opinions – an eavesdropping and Nazi-supporting neighbour, listening to their frequent and loud jokes at the expense of Hitler and Göring, had denounced the pair to the Gestapo. Ohser committed suicide the night before his trial and, attempting to mitigate the charges against Knauf, left a note in which he assumed all responsibility. This was to no avail as Knauf was sentenced to death the next day for ‘undermining military moral’ and ‘denigrating the Führer’ and was executed the following month.

Fig. 3, Erich Ohser, illustration for Father and Son

Fig. 4, Erich Ohser, Self-portrait, 1925,

pen and ink on paper

The portrait of Erich O’Krent is a record of happier times and of a friendship between two men, and indeed a third, who used their acute wit to courageously satire Nazism and who would pay the ultimate price. Kästner, outliving his friends by thirty years, said of Ohser: ‘We’re going to mourn him by celebrating his drawings’.[1]Indeed, Ohser (fig. 4), who left behind a wife and son, was a passionate and extremely talented graphic artist whose versatile skill spanned many techniques, styles and subjects and whose superb works continue to delight to this day.

[1] Eike Schulze, ‘Beloved & Condemned: A Cartoonist in Nazi Germany’ in The New York Review, 14 September 2017.