Anna Oelmacher (1908 –1991)

Further images

Female model in an interior with a vase of flowers and book

Signed and dated lower right: Oelmacher a / 1930

Oil on canvas

100.7 x 75.5 cm. (39 ½ x 29 ¾ in.)

Provenance:

Female model in an interior with a vase of flowers and book

Signed and dated lower right: Oelmacher a / 1930

Oil on canvas

100.7 x 75.5 cm. (39 ½ x 29 ¾ in.)

Provenance:

Private Collection, Stuttgart.

Hungarian Modernism is rarely seen outside of that country’s frontiers and is unsurprisingly therefore little known. This is a shame because, although by and large responding to artistic developments occurring to the West, in France and Germany, and to the East, in Russia, many of the Hungarian artists active at that time had innovative and individual things to say. Indeed, one only has to look at the output of artists such as Bertalan Pór, Sándor Bortynik, Vilmos Aba-Novák and Anna Oelmacher (fig. 1), author of the present painting, to realise that Hungarian artists of the 1920s and 1930s were capable of producing highly distinctive works through seamlessly synthesising outside elements and adding something very much of their own to the mix. That is certainly the case with Anna Oelmacher’s depiction of a nude model, which can be viewed as an important example of Hungarian Modernism by a highly original artist.

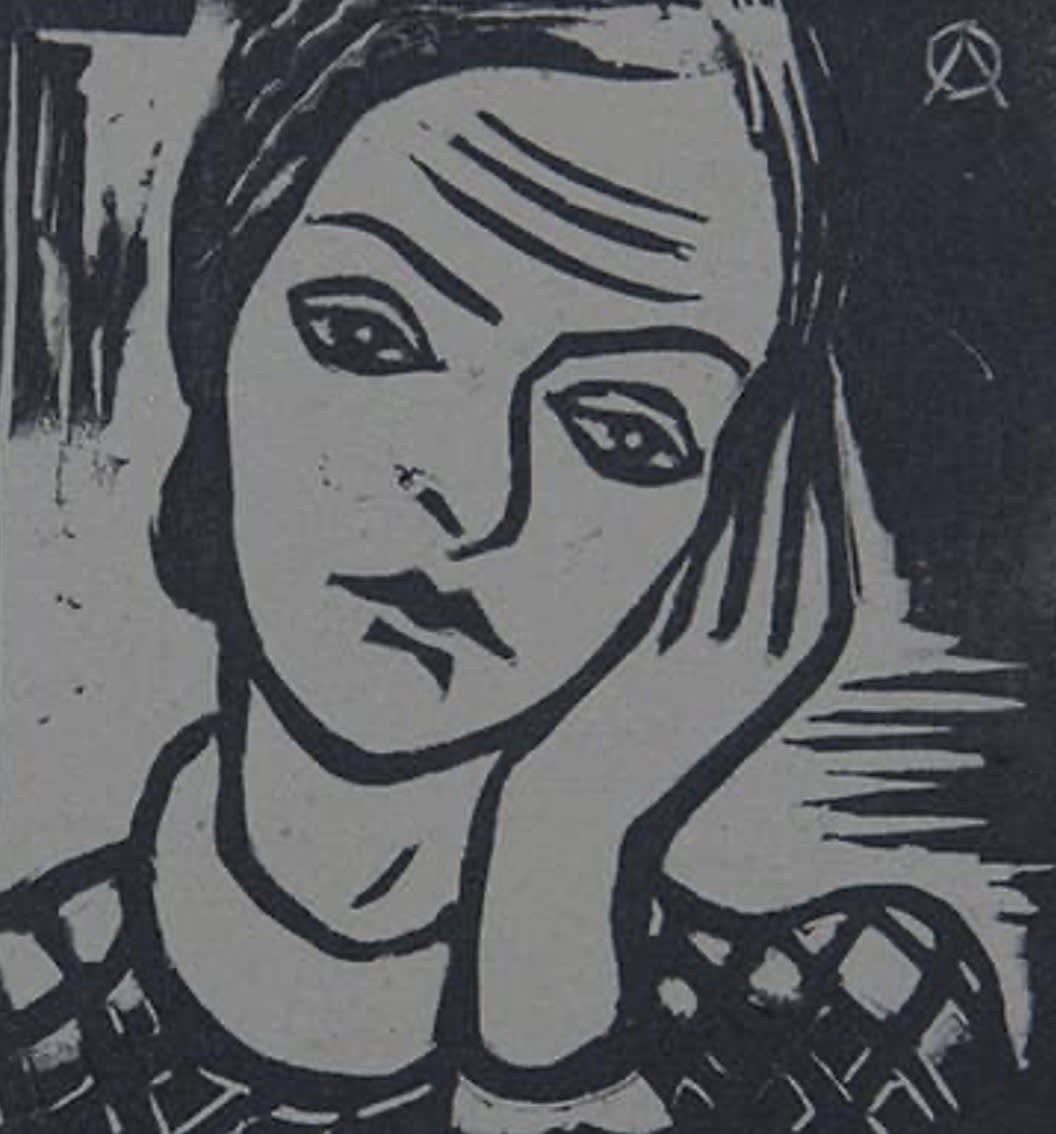

Fig. 1, Anna Oelmacher, Self-portrait

with paint brushes,1940, 66 x 50 cm,

oil on panel, Private Collection

Anna Oelmacher’s life encompassed almost the entirety of the 20th century, an extremely tumultuous period in Hungary’s history: over the course of her life, she would witness no less than eight different changes of regime.[1] Oelmacher was born in 1908 during the twilight days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire to a Jewish family in the predominately Jewish town of Füzesgyarmat, two-hundred kilometres south-west of Budapest. Clearly the young Oelmacher displayed artistic aptitude early on, as in 1924 she was sent to Budapest to study at the Applied Drawing School. She then went on to study textile design at the Hungarian Academy of Applied Arts, qualifying as an art teacher in 1930.

At around the same time Oelmacher studied painting at OMIKE, the Hungarian Jewish Educational Association which had been founded in 1909, amidst a growing climate of anti-Semitism, to provide learning and educational opportunities to poor Jewish students. Anti-Semitism would only intensify in Hungary under the fiercely conservative and nationalist government of Miklós Horthy (1920-1944), which scapegoated the Jews for, amongst other things, a faltering economy. In turn, increasingly harsh legislation was passed which limited Jewish participation in higher education and eventually in certain professional sectors. Aspiring Jewish artists, excluded from a fine arts education, were taught at OMIKE free of charge by renowned figures such as Adolf Fényes.

After the Second World War, during which Hungary had participated as an Axis power, the country was occupied by the Red Army and became a part of the Eastern Bloc. The advent of communism and the formation of the Hungarian People’s Republic in 1949 acted as a positive development in Oelmacher’s career, who just prior to the War had worked as an assistant to Aba-Novák and then as a designer in first a textile and later a paper factory. Jews suffered far less persecution, at least officially, under the Communist regime, and, importantly, Oelmacher had long displayed her Socialist credentials, having joined the Group of Socialist Artists as far back as 1934, when it was dangerous to have done so. Indeed, her graphic work from the 1930s, more anguished than her paintings, reflect, both allegorically and directly, Oelmacher’s fears for society under fascist rule (fig. 2).

Fig. 2, Anna Oelmacher, Self-portrait, 1934, 9 x 9 cm,

engraving, Dornyay Béla Museum

From the late 1940s, though she continued to exhibit her own works, Oelmacher switched her focus to academia and curation, working as a well-respected curator at the Hungarian National Gallery, becoming head of the graphics department in 1957. Organising numerous exhibitions on Hungarian artists, she also wrote import publications on Bertalan Pór and Adolf Fényes, amongst other artists she had known in her younger years. Oelmacher was awarded the Order of Merit for the Socialist Homeland and the Labour Order of Merit in 1967 and 1968 respectively, and in 1987, towards the end of her life, was granted the honorary title of Meritorious Artist of Socialist Culture. She died in 1991, two years after the fall of the Hungarian People’s Republic.

The present work depicts a nude female model with shimmering auburn hair in a sparse interior closed off by a recessed arch. The model sits on a simple wooden bench, her right foot resting on a book, with a blue vase containing a single white lily on the floor beside her. The choice of colours is harmonious and allows an interplay between the various elements, with, for example, the pink of the nipples juxtaposed against the pink wall and the whiteness of the lily emphasising the whiteness of the model’s skin. The construction of the space itself does not accord, intentionally, with the mathematical realities of perspective. The painting dates to 1930, and is therefore one of Oelmacher’s earliest known works, from a time when the young artist was approaching the end of her studies. Already in evidence is Oelmacher’s interest in simple line and blocks of colour, elements which would remain constants throughout the rest of her career.

Clearly the female model in a studio setting was of particular interest to Oelmacher at this juncture, since there are two other known depictions of the subject dating to 1930 (figs. 3 and 4). Both are of smaller format and show a standing nude female model next to a window. Presumably the model in these two paintings, with her bobbed haircut, is a different sitter to the seated figure in the present work. Though all three demonstrate similar concerns with line, colour and form, the present work is the simplest in its use of space and volume: for example there is no real use of shading to modulate the surfaces of the model’s body. That said, because of this, it is paradoxically the most sophisticated and well-thought out of the three, and the most satisfying in terms of its compositional arrangement and visual impact. Therefore, though impossible to say with any certainty, the painting may be the culmination of Oelmacher’s experimentation with this subject of the model in the studio.

Fig. 3, Anna Oelmacher, Model in the studio, 1930,

77 x 64 cm, oil on canvas, Private Collection

Fig. 4, Anna Oelmacher, Model in the studio, 1930,

60 x 50.5 cm, oil on canvas, Private Collection

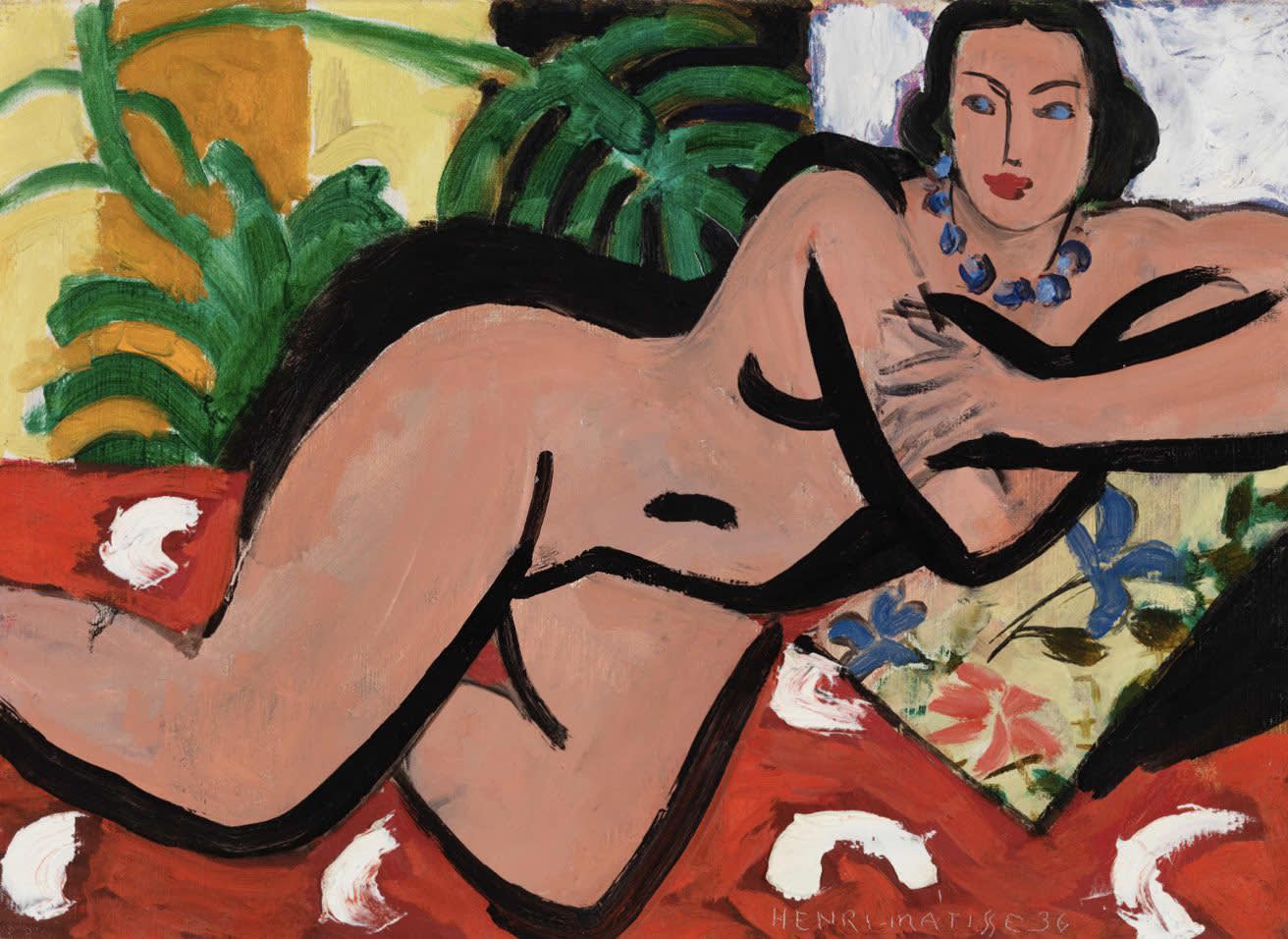

The painting clearly shows Oelmacher’s interest in the work of some of her European contemporaries, perhaps above all Matisse, who had been meditating on the nude model since the opening years of 20th century and who, by the 1930s, had reduced his forms to blocks of line and colour, in much the same way as the young Hungarian artist was doing (fig. 5 ). A potential interest in the metaphysical cityscapes of Giorgio de Chirico can also be sensed in the pervading aura of stillness and the illogical perspective inherent in Oelmacher’s work, though this may have been mediated through the Hungarian precedent of Sándor Bortnyik’s The New Adam of 1924 (fig. 6). Looking further back into the past, one wonders whether Oelmacher was influenced in some ways by Quattrocento depictions of the Annunciation (fig. 7.), with the cold palette, arches, seated female figure and lilies all reminiscent of the Biblical scene. Yet, despite these various interests, Oelmacher’s work is deeply individual and original, referencing but never imitating other sources, and should be considered an important example of Hungarian Modernism. Hopefully more of her idiosyncratic and impactful work will come to light in the future.

Fig. 5, Henri Matisse, Nu (Carmelita), 1904, 81 x 59 cm, oil on canvas,

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Fig. 6, Sándor Bortnyik, The New Adam, 1924, 48 x 38 cm,

oil on canvas, Hungarian National Gallery

Fig. 7, Fra Angelico, The Annunciation, 225 x 200 cm, fresco,

San Marco, Florence

[1] These were: Kingdom of Hungary as part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1918; First Hungarian Republic, 1918-19; Hungarian Soviet Republic, 1919; Hungarian Republic, 1919-1920; Kingdom of Hungary, 1920-1946; Second Hungarian Republic, 1946-49; Hungarian People’s Republic, 1949-1989; Third Hungarian Republic, 1989 onwards.