Frank Dobson, R.A. (1886 – 1963)

Head of a girl, probably Jacynthe Underwood

Signed and dated lower right: F. DOBSON / 32

Red chalk on paper

35.5 x 25.5 cm. (13 ¾ x 10 in.)

Provenance:

Head of a girl, probably Jacynthe Underwood

Signed and dated lower right: F. DOBSON / 32

Red chalk on paper

35.5 x 25.5 cm. (13 ¾ x 10 in.)

Provenance:

The Artist’s Estate;

Gillian Jason Gallery.

Though long considered one of Britain’s great 20th-century sculptors, Frank Dobson has to some extent been overshadowed by international titans such as Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth. Yet in recent years the importance of his highly original vision has come to be increasingly recognised and lauded, with the strength and simplicity of his forms pleasing to the modern eye, as witnessed by the intense interest in Dobson’s Female Torso (fig. 1) of 1926, which appeared on the market last year.

Fig. 1, Frank Dobson, Torso, 1926, carved sandstone,

H 41 cm, Private Collection

Like many sculptors, drawings were always a vital part of the creative process for Dobson. Though they hold their own as unique objects, they were not produced to stand alone: as Dobson himself explained in the late 1930s, ‘my attitude to drawing has been governed by the fact that I was drawing to get information which would help me to make sculpture’.[1] When he later taught at the Royal College between 1956 and 1953, one of Dobson’s students, John Bridgeman, recalled the sculptor’s unique graphic approach: ‘His method of drawing was interesting to watch, for the hand holding the conte would tremble like a butterfly and become strong and firm on reaching the paper’.[2]

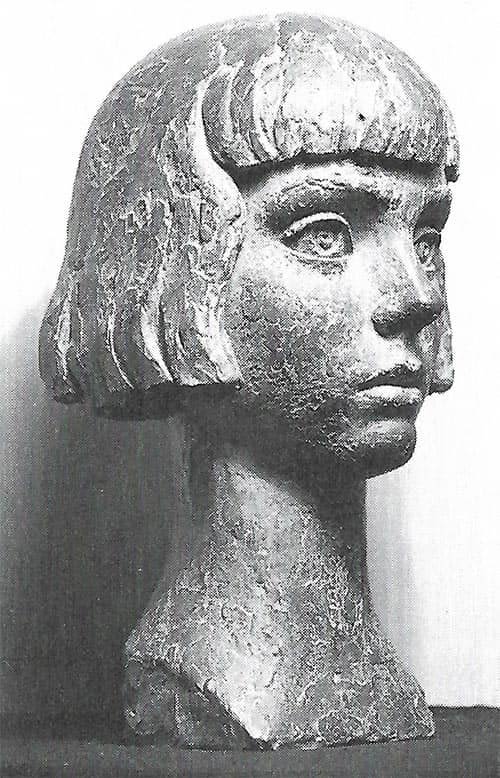

Fig. 2, Frank Dobson, Jacynthe Underwood,

1930, bronze, H 38 cm, Private Collection

Fig. 3, Constantin Brancusi, Danaïde, c. 1918,

bronze on limestone base, H 40.5 cm, Tate

The model in the present work is most likely Jacynthe Underwood, daughter of the author Eric Underwood, a friend of the artist. Her fashionable bob haircut and distinctive features accord very closely with a bust of Jacynthe from 1930 (fig. 2). Certainly there is a directness which would seem indicate a connection with the model: here, as with much of his best sculpture and graphic work, Dobson almost paradoxically balances monumentality with intimacy. In the spherical forms one might detect a debt to Brancusi (fig. 3), who was a friend of Dobson. The solidity of the head may also reflect the sculptor’s keen interest in Picasso’s relatively recent neo-classical portraits, which had greatly impressed Dobson when he visited Paul Rosenberg’s gallery in Paris a few years before. Less tangible perhaps, and looking back to the more distant past, one might detect the stylised and oval forms of Francesco Laurana (fig. 4).

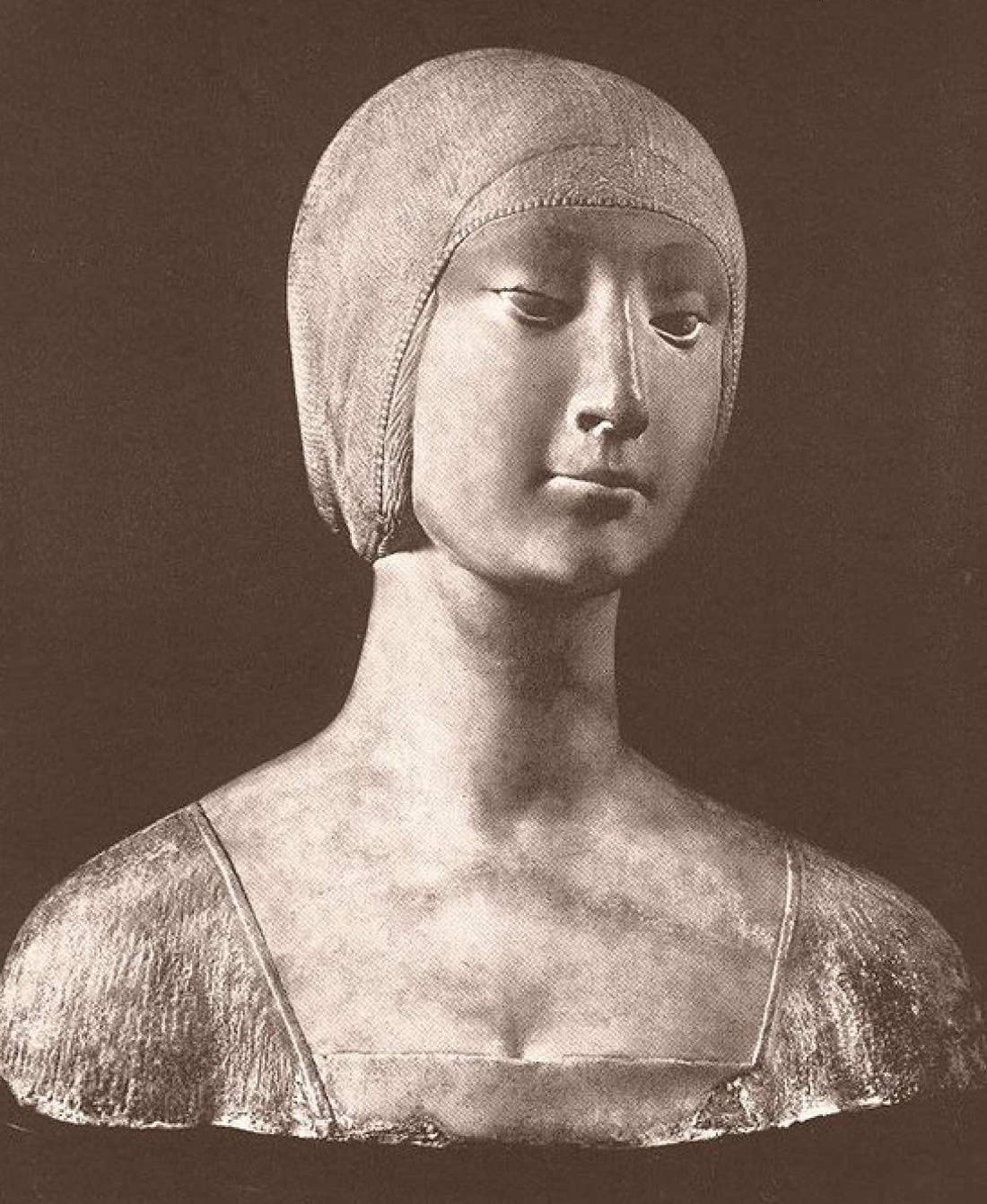

Fig. 4, Francesco Laurana, Bust of a young

woman, marble, Musée du Louvre